Moors of Europe

Etymology

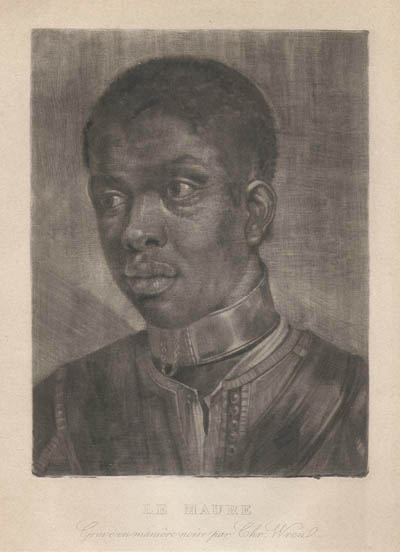

Variants of the term "Moor" have been used by many Europeans since ancient times as a general description for indigenous Africans. Contrary to popular belief, the term is not synonymous with "Islamic" or any specific Arab or African religion, civilization, or ethnicity.

|

One need not be a linguist to see the word's evolution from the Greek "mavro" to the Latin word, "mavrvs" (actually, "mavro" in the ablative, singular, masculine Latin form). The English transliteration is "Maurus" and the plural form is "Mauri," specifically used by ancient Romans in reference to Black Africans. Writers in both Greek and Latin specifically used the term as a racial identity. In the Epitome de Caesaribus (390s AD), we learn that Aemilianus was "a Moor by race." Procopius of Caesarea (500-565 AD), a Byzantine scholar who wrote in Greek, said in his History of the Wars, "beyond that there are men not black-skinned like the Moors..."

Even through the middle ages, the term (as well as the Spanish, "moro," the German "mohr," the Dutch "moor" etc.) continued to be used in reference to Black Africans. For example, in one of the oldest Dutch texts, Lancelot-Compilatie (1300s AD), a Moor was described specifically as "black."

- "Maurus" was synonymous with "Moor," "negro," and "Aethiops" in John Etick's A new English-Latin dictionary (1783)

- In A new Latin-English dictionary by William Young (1810), "Maurus" is a "black Moor"

- According to the Ainsworth's Latin Dictionary, Morell's abridgment by Alexander Jamieson, Robert Ainsworth (1828), "Maurus" means "black Moor"

The English term "Moor" also meant "Black" in English dictionaries and encyclopaediae prior to the 20th century:

- "Moor" meant "negro" or "black-a-moor" in A Dictionary of the English Language (1768) by Samuel Johnson

- The Encyclopaedia Londinensis (1817) by John Wilkes lists "moor" as follows: "[maurus, Lat. μαυρο, Gr., black.] a negro; a blackamoor."

- John Olgilvie's The Imperial Dictionary of the English Language (1882), a Moor was a "black man or negro"

Even the UK National Archives concurs with this assessment:

In recent years, however, a number of revisionists (including wikipedia editors) have decided to deliberately misrepresent the words "Maurus" and "Moor" to simply mean Arab, Muslim and/or Berber--a grave contrast to historical precedent.

Misconceptions about Etymology

Contrary to popular belief, the English word "moor" does not descend from "Almoravid," the name of the dynasty that controlled much of present-day Morocco, Mauritania and Southern Spain from 1040 to 1147 AD. Almoravid is actually the anglicized version of the Arabic name, Al-Murabitan, which roughly means "those who are ready to defend." As aforementioned, the Latin and Greek versions of the word "moor" were used several centuries prior to the existence of the Almoravid dynasty. According to Arab historians during the dynasty's reign, the Almoravids were not even native to Africa, but from Arabia.

Moors In Ancient and Medieval European History

|

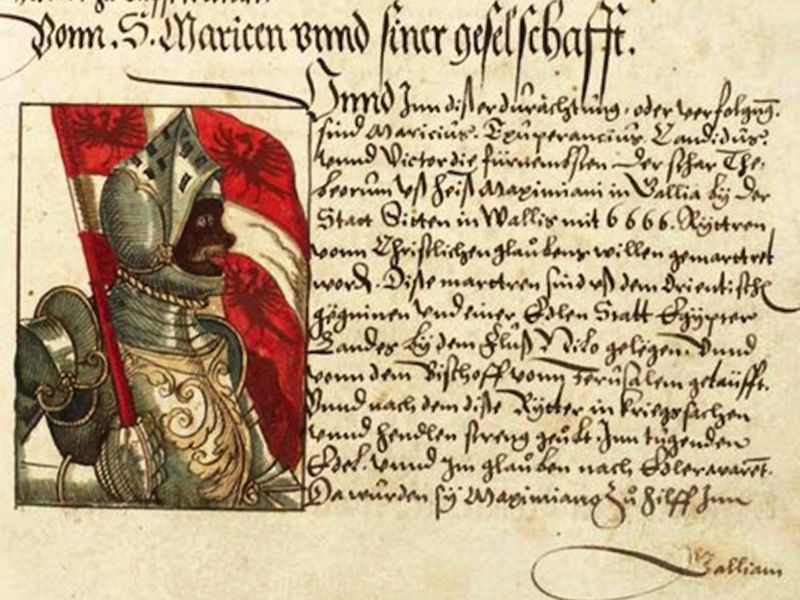

Other skilled Africans were made Catholic patron saints, such as the popular St. Maurice or Mauritius in Latin as described in the Passio Martyrum Acaunensium (The Passion of the Martyrs of Agaunum) by French bishop St. Eucherius (434-450 AD). According to the text, St. Maurice lived around 286 AD and was believed to be part of the Theban Legion of Egyptian Christians who served in the Roman army under his command. St. Maurice's brigade was supposedly decimated for disobeying orders to kill Christians in Roman Helvetia (Switzerland). The oldest known physical representation of him, however, was not created until 1281 AD (a detailed statue now housed in the cathedral of Magdeburg, Germany; shown on the right).

|

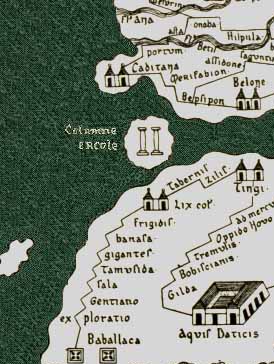

By 470 AD, following the fall of the Roman empire, Africans slowly began repopulating southern Europe, and by 711 AD, General Tarik ibn Ziyad al-Gibral (or Tariq bin Abdullah bin Wanamu al-Zanati), an Islamized African native whence the name, "Gibraltar," is derived, led a major invasion beyond that same peninsula. It is clear Tarik was African. Al Idrisi (1099-1161 AD), a cartographer and Egyptologist who lived in Sicily (his family descends from the Arab Idrisids who conquered Morocco and Southern Spain in 788 AD), referenced him as Tariq bin Abd 'Allah bin Wanamu al-Zanati. The "al-Zanati" refers to the Zenata people of Northwest Africa.

Tarik's fortress (shown below) is the earliest known medieval castle in Europe, built centuries before those of the Loire Valley in France. As legend has it, the phrase, "Thank heaven for 711" comes from the age of enlightenment ushered in when Moorish civilization permeated the Iberian peninsula (Spain, Portugal and Andorra) and Southern France, leading Spain into an unprecedented era of freedom of association, religion, education and enterprise.

|

|

|

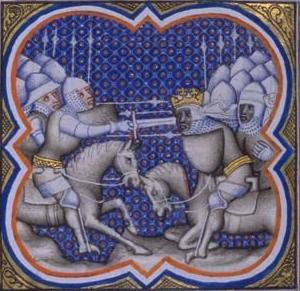

"Although Marsile has fled, his uncle Marganice remains, he who rules Carthage, Alfrere, Garmalie, and Ethiopia, an accursed land. He has the black people under his command, their noses are big and their ears broad, together they number more than fifty thousand. They ride fiercely and furiously, then they shout the pagan battle cry."

|

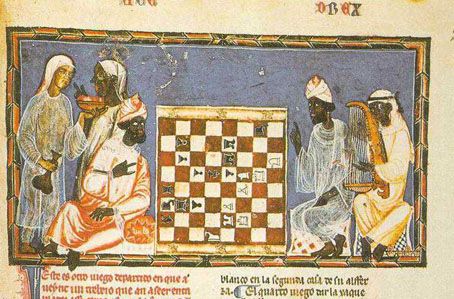

Medieval Christian rulers in the Iberian peninsula waged a similar campaign to control the region, and Moors were depicted in numerous manuscripts characterized by the mass persecutions and religious conversions that occurred in that era. For example, the famous Cantigas de Santa Maria, written in the court of Alfonso X of Castile circa 1280, illustrates a scene of a Moor being saved, baptized and converted to Christianity. Another scene shows a noble woman using her Moorish servant to frame for adultery her daughter-in-law. The pair is arrested and sentenced to burn at the stake, but the woman's life is spared miraculously while the Moor burns in flames.

|

|

|

|

The manuscript, Vidal Mayor by Michael Lupi de Çandiu (1290-1310), also illustrates conversions to Christianity through scenes of Moors being captured by soldiers and brought before a king (likely Jaume II of Aragon) and being baptized.

|

|

There were also several documented accounts of Moors in northern and central Europe, including that of the so-called "Freising Moor." The oldest known use of his image on any coat of arms was created around 1300 AD by Bishop Emicho of Wittelsbach in Skofja Loka, Slovenia. The town of Freising, Germany's oldest known coat of arms dates to 1362, which included the head of the Moor along with the bear he supposedly defeated while traveling with Bishop Abraham of Freising. The legend says that Freising's Moor was a servant, however, the crown atop his head may refute said legend. The archdiocese of Munich, Pope Benedict XVI, and several Bavarian municipalities continue to use depictions of the "Freising Moor" on their official coats of arms, a testament to the presence and authority of Moors in medieval Europe. After all, there are numerous accounts of Moors ruling areas of Europe as mentioned above in France and even in Germany, as depicted in the tapestry, "Wild men and Moors," showing the ruling Strasburger family defending their castle against "wild men" with pale skin.

|

|

|

|

In the 1490s AD, Catholic rulers had begun to rid the Iberian Peninsula of much of its large Islamic Moorish population (as well as other people who practiced non-Christian religions such as Judaism). After waging a long war on Granada, Spain's Ferdinand V and Isabella I seized control of that region in 1492, promising to keep religious freedom. However, Cardinal Francisco Jimenez Cisneros began a large-scale Inquisition in 1499, including mass coversions to Christianity, persecutions, book burnings, and closing mosques and synagogues, and by 1502 Ferdinand and Isabella expelled all non-Christians, which included many Moors (but not necessarily Christianized Moors).

Portugal's King Manuel also expelled non-Christians, many of whom were Moors, by royal decree in 1496. The result was that some relocated to other parts of Europe where they became high ranking nobility as their knowledge and skill continued to be highly valued. Although most Moorish families of nobility (the origin of the term "Black Nobility") intermarried with Europeans, their surnames continued to link to their African heritage. Family names such as Moore, Morris, Morrison, Morse, Black, Schwarz (the German word for "black"), Morandi, Morese, Negri, etc. all bear linguistic reference to their African ancestry. For example, the oldest Schwarz family crests even depict the image of an African, or "Schwarzkopf," ("black head" in German). Other families and municipalities adopted similar coats of arms which continue to exist in some form, demonstrating the important role Africans played in European history.

Continue >>