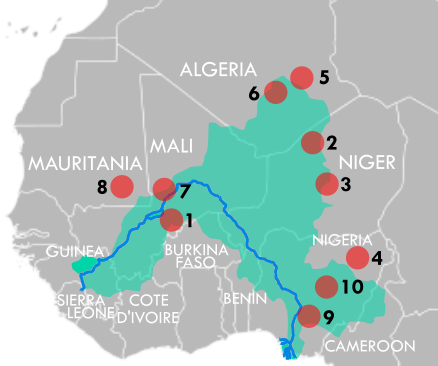

Development of Niger Valley

Civilization

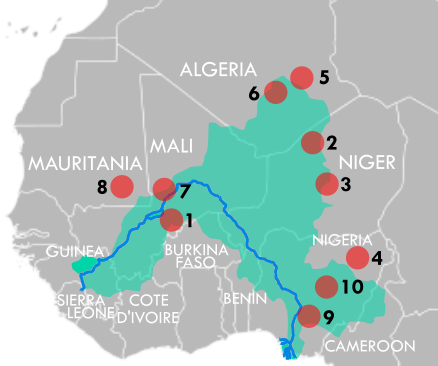

(credit: AncientAfricanHistory.com)

1. Ounjougou (9400 BC) - early pottery

2. Dabous (8000 BC) - largest ancient petroglyphs

3. Gobero (7550 BC) - early graveyard, early aqualithic culture

4. Dufuna (6500 BC) - 2nd oldest dugout canoe

5. Tassili N'ajjer (6000 BC) - early boats, domesticated cattle, horses

6. Oued Mertoutek (3000 BC) - early writing

7. Lower Tilemsi Valley (2500 BC) - oldest domesticated millet

8. Dahr Tichit (2000 BC) - early city

9. Lejja (2000 BC) - oldest iron smelting

10. Nok (1500 BC) - early iron smelting, terracotta statues

|

Niger Valley Civilization

The Niger Valley refers to the 2,597-mile Niger River's watershed and its environs, a vast region spanning

the lush Delta region of Southern Nigeria, north to the dry highlands of Southern Algeria, and west to the lush highlands of Guinea.

Contrary to popular belief, this region of West Africa has been inhabited for tens of thousands of years. The Niger Valley, in particular,

lies south of Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, where archaeologists recently found the world's oldest early modern humans (300,000 BC), and north of

Iwo Eleru, Nigeria, where 13,000-year-old human remains have been found.

And despite widespread ignorance of West African history, there is an abundance of archaeological evidence and

written accounts available to help us trace the development of this region's advanced ancient and medieval civilizations. Early Niger Valley

societies were the first to practice ceremonial burials, domesticate millet and smelt iron, and were among the firsts to write, make pottery,

domesticate cattle, and use boats for travel. Their industries and strong trading networks gave rise to

wealthy empires and city-states whose stone, earthen and walled cities were intellectual

hubs of the medieval world.

Early Pottery

Archaeologists from the University of Geneva dated pottery

sherds discovered at the Ravin du Hibou site at Ounjougou, Mali to 9400 BC, making them among the oldest ceramics in the world

(only pottery found in Sudan, Japan, China and Siberia,

The Dabous Giraffes in Niger (8000 BC) (credit: Bradshaw Foundation)

|

which are generally dated to 10,000-12,000 BC, are supposedly older).

Located in the Valley of Yamé (west of the Inner Niger Delta), the ancient, so-called Ounjougou culture lived where the Dogon people reside today. And similar to their

current use of ceramics to boil grains and cereal, archaeologists posit that the ancient pottery was used for the same purposes.

World's Largest Ancient Petroglyphs

The Tenere Desert in Niger is home to over 800 ancient rock carvings that depict humans and animals, including the largest ancient

petroglyphs in the world. At Dabous, about 150 miles north of Agadez, lie detailed rock carvings of life-size

giraffes, the largest of which is 18 feet long (adult giraffes are generally 15-20 feet tall). Archaeologists date

the petroglyphs to 8000 BC, an era when the Tenere Desert was likely greener (as further explained below) and more hospitable for both

giraffes and humans.

Early Aqualithic and Pastoral Civilization; Early Graveyard

Farther south at Gobero, also in Niger's Tenere Desert, archaeologists from

the University of Chicago uncovered the remains of an advanced civilization that dates

to 8000 BC and continuously occupied this site for nearly 5,000 years (so-called "Kiffian Culture"). This site

provides one of the earliest examples of domesticating cattle and practicing ceremonial burials, with one of the

oldest graveyards in the world. Moreover, numerous ancient harpoons, fish hooks and pottery with wavy lines, which

archaeologists generally associate

with pre-historic populations that heavily fished, were among the oldest artefacts identified at the site. There were also

the 8,250-year-old remains of catfish, tilapia and hippos, further evidencing that the climate was once much more humid

than today.

Pottery shard with wavy lines (8000 BC) (credit: Paul Sereno)

|

One of many harpoons found at Gobero (8000 BC) (credit: Paul Sereno)

|

The Dufuna Canoe (6500 BC) being hoisted out of the ground; currently housed at the National Museum at Damaturu, Nigeria (credit: Peter Breunig)

|

Second Oldest Known Boat in the World

Heavy fishing and riparian hunting led early Niger Valley civilizations to boating over 8,500 years ago. One of the oldest boats

ever found anywhere in the world, the so-called Dufuna Canoe (6500 BC), was partially discovered by a Fulani cattle herdsman digging

a well near Dufuna, Nigeria. This site is not far from the Komadugu Gana River, a tributary of Lake Chad, which would have been

much larger in that era. Measuring 27.6 feet long, the Dufuna Canoe is nearly 3 times the length of and carved in a more sophisticated

manner than the so-called Pesse canoe, which was found in the Netherlands

and is believed to be the only boat older than the Dufuna canoe. The Dufuna discovery demonstrates ancient Nigerians' early use of advanced

technology and possibly maritime trade.

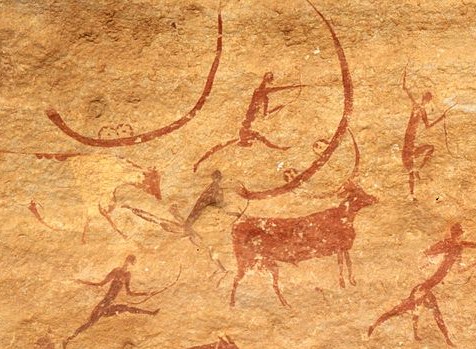

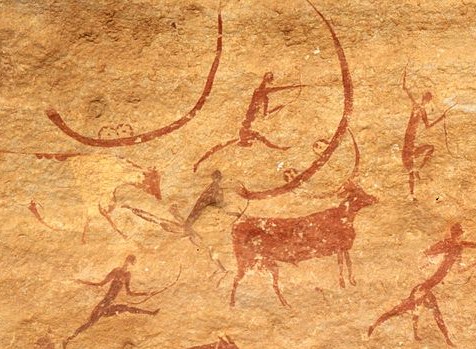

Early Depictions of Boats and Domesticated Cattle

Rock art depicting boats and domesticated cattle at Tassili N'Ajjer, Algeria (6000 BC) (credit: Gruban)

|

Depictions of boats also appear around 6000 BC in Saharan rock art at Tassili N'Ajjer in Southern Algeria, which hosts

roughly 15,000 ancient rock drawings, some dating as far back as

12,000 BC, but most dating to 6000 BC.

Such boats appear alongside the images of people using

bows and arrows, suggesting boats may have been used for hunting or early naval warfare.

Recent studies have also shown that the Sahara may alternate between

20,000-year wet and dry cycles,

so the desert would have been replete with rivers and lakes during the time the rock paintings were drawn.

The numerous depictions of longhorn domesticated cattle, which feed off grass, provide further evidence that this desert

was once green. Such rock paintings of humpless, longhorn cattle predate all others outside Somalia (i.e. Laas Geel) and are

generally considered by archaeologists to represent the domesticated Bos Taurus species. Such depictions demonstrate that

domesticated cows were present in Africa as early or earlier than in Asia.

Early Writing

Ancient Tifinagh inscription on a rock in Essouk, Mali (c. 200 BC) (credit: Tagelmoust)

|

Inscriptions of an ancient African writing system called the Tifinagh or Libyco-Berber or Mande script

can be found on rocks and pottery

all over the southern Sahara and the Niger Valley, including at Oued Mertoutek and Tassili N'ajjer in Algeria, Essouk in Mali, Dahr Tichit in Mauritania and Ibel, Niger.

The script has been used for thousands of years to write in Mande, Tamazight,

Numidian, and other languages of the Niger Valley and greater Sahara region. One of the first attempts to radiocarbon date the writing was carried out by

A.E. Close in 1980, who dated to 3000 BC pottery and rock paintings at Oued Mertoutek in Southern Algeria. The widespread use of this ancient script is evidenced

by its appearance at numerous sites as mentioned above and is still used by Amajegh (Taureg people), who mainly inhabit the Niger Valley and Sahara, including present-day Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso,

Southern Algeria and Southern Libya, and are the only known group of Tamazight speakers who have used the Tifanagh

script continuously since antiquity (in recent years, however, the larger Tamazight speaking community of

the Sahara region have recently adopted use of the Tifanagh script). This long history of writing helped pave the way for the medieval world's

largest literary industry in the Niger Valley, as further described below.

Early Agriculture

West Africa is home to the world's oldest evidence of

domesticated millet, attesting to the region's

long history of agriculture. Dating back 4,500 years, the cultivated millet was identified by University College London archaeologists

at a site in Mali's Lower Tilemsi Valley and is centuries older than examples found elsewhere in Africa and Asia. Farther west,

archaeologists identified more evidence of domesticated millet dating to 2000 BC at

Dahrs Tichit and Walata in southern Mauritania and hundreds of miles away in Birimu, Ghana, which shows the great

extent of neolithic agriculture in West Africa.

In addition to millet, early civilizations in this region widely cultivated rice.

And recent analyses of rice genomes make it clear

that African cultivated rice (Oryza glaberrima) was domesticated independently from the more globally popular Asian rice (Oryza sativa).

Researchers even pinpointed the Inner Niger Delta (i.e. the portion of the river between Timbuktu and Djenne-Djenno) as the most likely birthplace of African rice at least 2,000 years ago, with

the oldest evidence from ancient city of Djenne-Djenno in Mali.

Such findings shatter longheld misbeliefs that African rice was derived from Asian rice brought to West Africa much later in history.

A Nok terracotta statue (195 BC)

|

Oldest Iron Smelting and Early Terracotta & Bronze Sculpture

Ancient Niger Valley civilizations widely practiced advanced metallurgy and sculpting. In Lejja, a town in the Niger Delta region of

Southern Nigeria, archaeologists have radiocarbon dated iron-smelting

furnaces to 2000 BC, making them the oldest in the world. Evidence of iron smelting and terracotta pottery

have also been found north of the confluence of the Niger and Benue Rivers in Nigeria, where the so-called Nok

culture thrived as early as

1500 BC. In the Taruga valley alone, 13 ancient iron smelting furnaces,

along with ancient iron tools and weaponry have been identified.

And in Taruga, Samun Dukiya, Jos, Sokoto, and Nok in particular,

hundreds of intricate terracotta statues have been uncovered, some dating as far back as 1000 BC--centuries older than any known Greek sculpture. The Nok statues depict men and women wearing ornate

costumes and jewelry--some on horseback, others in symbolic and abstract gestures and poses. Eventually the popularity of sculpting

in

clay gave way to iron and bronze. At numerous archaeological sites in Southeast Nigeria, such as Igbo-Ukwo, there are

hundreds of examples of 1,200-year-old, intricate bronze sculptures using advanced methods that Europeans did not learn until the 1500s.

Terracotta statue of a woman (200 BC) (credit: Siyajkak)

|

Terracotta statue of a man (200 BC)

|

Bronze vessel in the shape of a conical shell, found at Igbo-Ukwu (800) (credit: Ochiwar)

|

Bronze ornament found at Igbo-Ukwu (800) (credit: Ochiwar)

|

Famous Ife heads made of brass and designed in a naturalistic style (1300s) (credit: Trustees of the British Museum)

|

In addition to iron and bronze, sculpting in other metals such as copper, lead, zinc and alloys such as brass (copper/zinc)

gained popularity throughout medieval times, especially in the industrial

cities of the lower Niger Valley. Large-scale production of metallic sculptures and other objects like agricultural and hunting tools and

weaponry, fueled the growth and influence of the chief Yoruba city of Ife and the Edo city of Benin. In this part of the Niger Valley, in particular,

metalworking was considered to be a ritualistic practice and blacksmiths were highly valued and honored professionals.

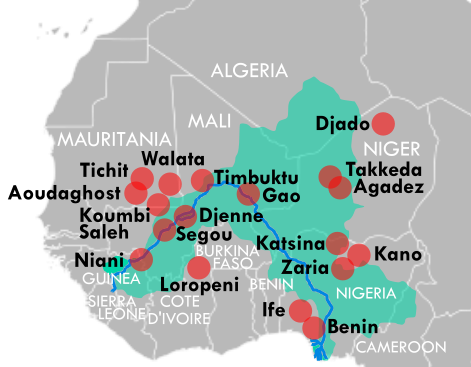

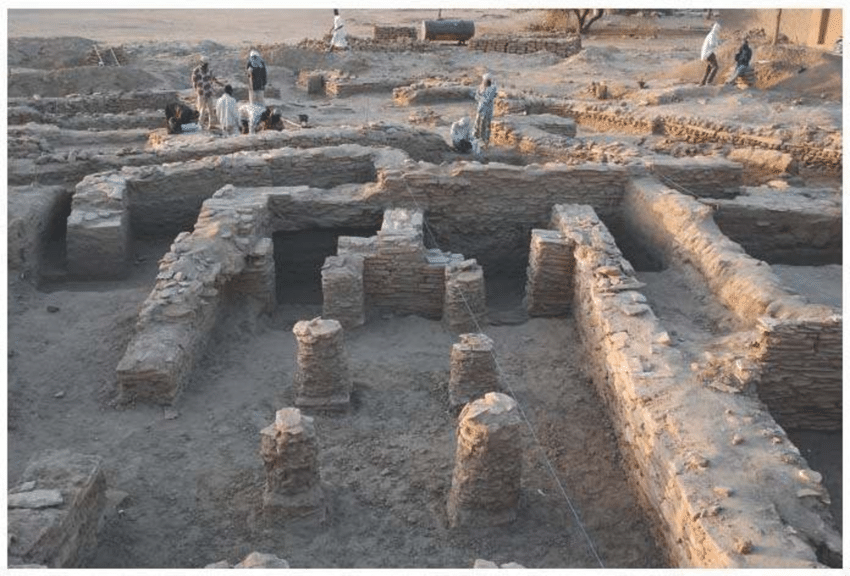

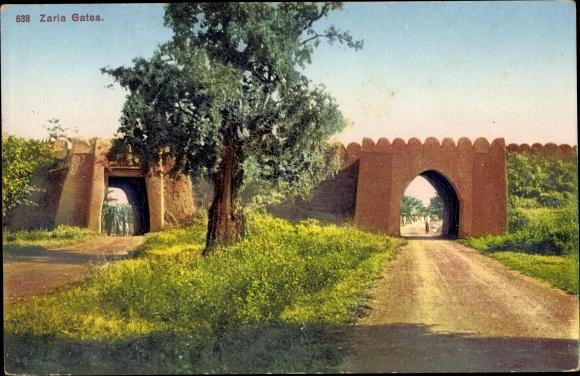

Medieval Cities and the Rise of Empires

Other ancient agrarian and industrial Niger Valley towns grew into wealthy centers of trade due to their strategic location between the mineral mines to the

south and the salt mines in the Sahara. While some major cities, especially Kano, Katsina and Zaria in Hausaland, maintained their

independence, other major cities were unified under

the first documented empires in the Niger Valley, most notably Wagadu or Ghana (700-1240), Benin or Edo (1000s-1897), Mali (1235-1670)

and Songhai (1464-1591). In fact,

pottery from Egypt and as far away as China

were found while excavating the Wagadu capital city of Gao--a testament to its far-reaching trade networks (archaeologists

at other sites, such as Yikpabongo in northern Ghana (the modern-day

country, not to be confused with the Ghana Empire), have even found

evidence of the medieval use of bananas and pine, which are

not native to the Niger Valley.

The wealth of this region was well documented throughout the medieval world. Although originally called "Wagadu" by founding

Emperor Kaya Maghan (700), the more widely known name, "Ghana", comes from Iraqi

scholar Ibrahim al-Fazari (777), who called it the "land of gold."

Al-Hasan ibn Ahmad al-Hamdani (893-945 AD), a Yemeni geographer and historian, also described Ghana

as having the "richest gold mines on earth."

Mansa Musa, emperor of the Mali Empire, on the Catalan Atlas (1375)

|

Al Bakri, a historian and geographer from Cordoba (former caliphate in Spain), also said, "On every donkey-load of salt the King of Ghana levies one golden dinar when it is brought into his country and two dinars when it

is sent out." And Mali Emperor Mansa Musa I (1280-1337) was famously depicted with a golden crown and coin

in the Catalan Atlas

(possibly written by Iberian cartographer Abraham Cresques in 1375) and is widely considered the wealthiest historic

figure in the world. Despite their mineral wealth, Niger Valley cities would become even more famous for

their large collections and trade of scholarly books, especially Timbuktu, which was described by Malian scholar, Mahmud

Kati (1468-1552), in his Tarikh al Fettash as a city with

"solid institutions, political liberties, purity of morals...courtesy and generosity towards students and scholars" -- making it an

international intellectual mecca unrivaled in the medieval world.

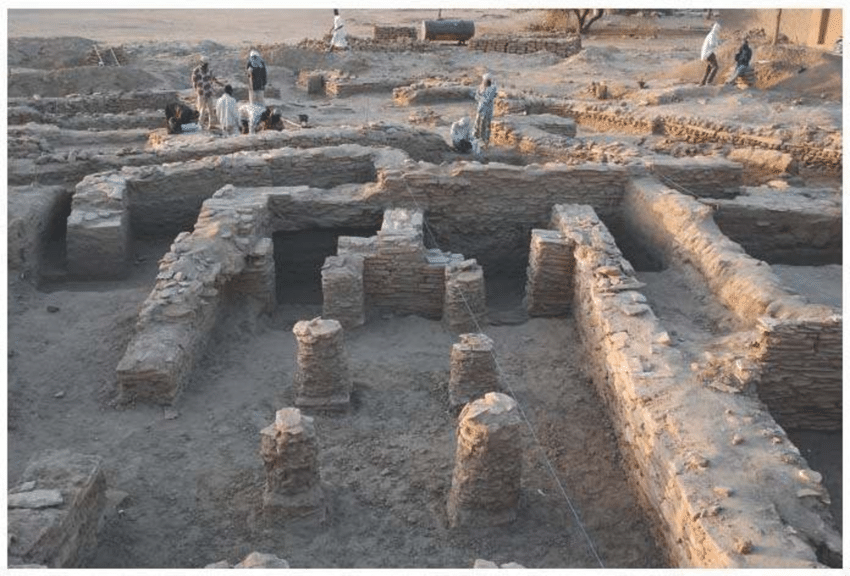

Stone ruins of Gao, a capital of the Wagadu Empire (900) (credit: Mamadou Cisee, Shoichiro Takezawa)

|

Stone ruins of Kumbi Saleh, the first capital of the Wagadu Empire (700) (credit: Serge Robert)

|

Mosque of Tichit, Mauritania (1100) (credit: Ville de Tichitt, Mauritanie)

|

Medieval stone buildings in Tichit (1000), a major Soninke city that was settled by 2000 BC and was part of the Wagadu, Songhai and Mali empires (credit: Ville de Tichitt, Mauritanie)

|

Gate of the original earthen wall encircling Kano, Nigeria (1000)

|

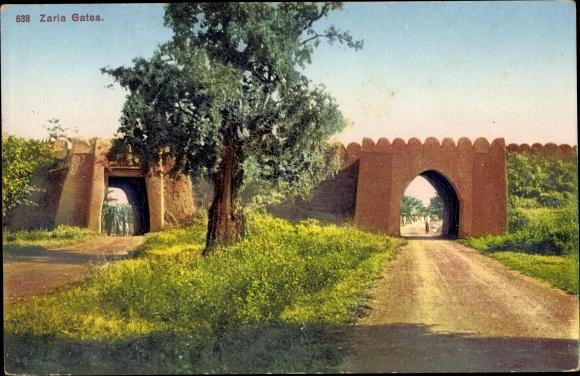

Gates of the original earthen wall that encircled Zaria, Nigeria (1000)

|

Reconstructed gateway to Gidan Rumfa, the emir's palace in Kano (1475)

|

A busy street in front of medieval buildings in Kano, Nigeria (founded in 999)

|

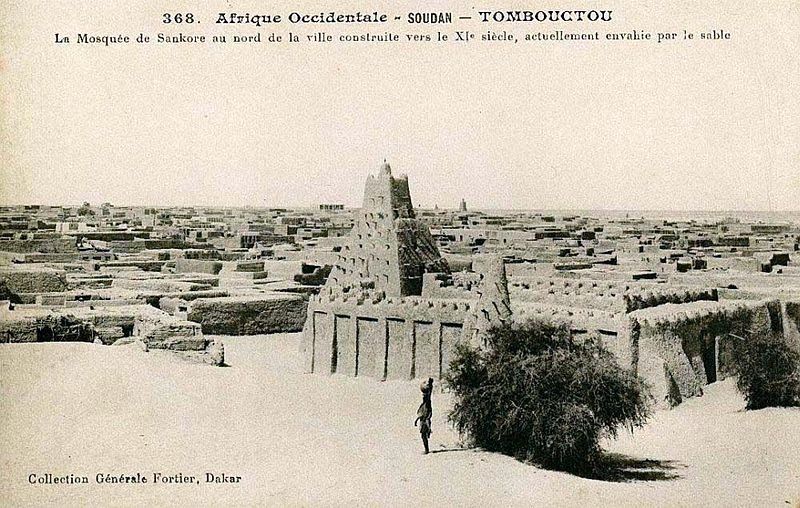

Second Oldest University (outside of the Nile Valley)

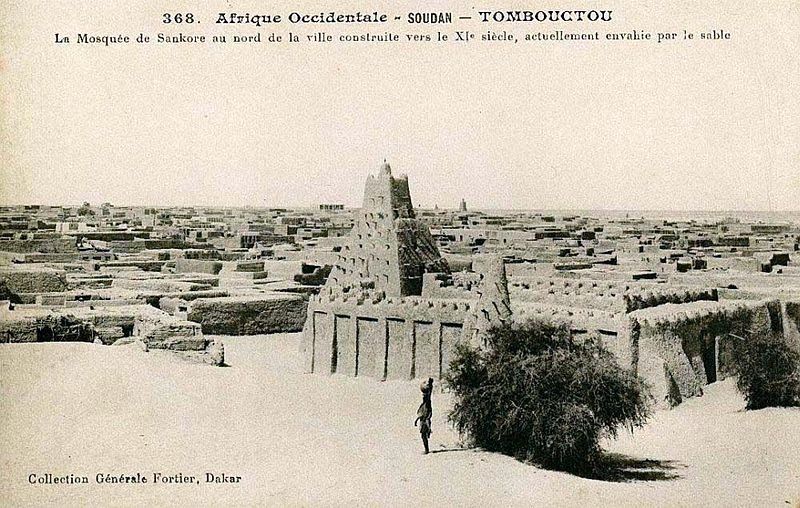

University of Sankore, with the medieval city of Timbuktu in the background

|

Timbuktu is also the site of the world's second oldest university (excluding ancient Nile Valley temples), established in

989 as the University/Mosque of Sankore Madrasah. At its height, the university enrolled 25,000 students and housed up to 700,000

books--more than anywhere else

in the medieval world. Contrary to popular belief, the iconic pyramid-like structure is made of

cut stone (not mud brick), covered with a mud stucco that is periodically stripped and renewed--a practice that keeps the interior cool during the day and warm

at night.

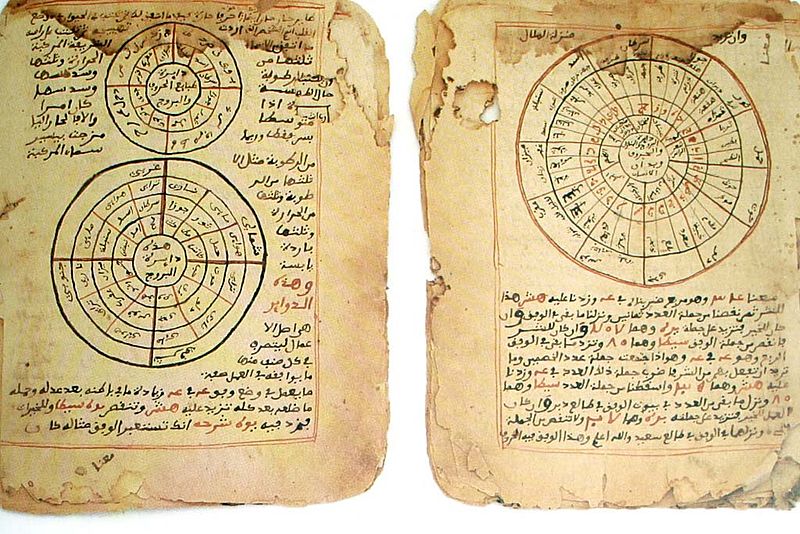

Medieval manuscripts from the Djenne Library (credit: Sophie Sarin)

|

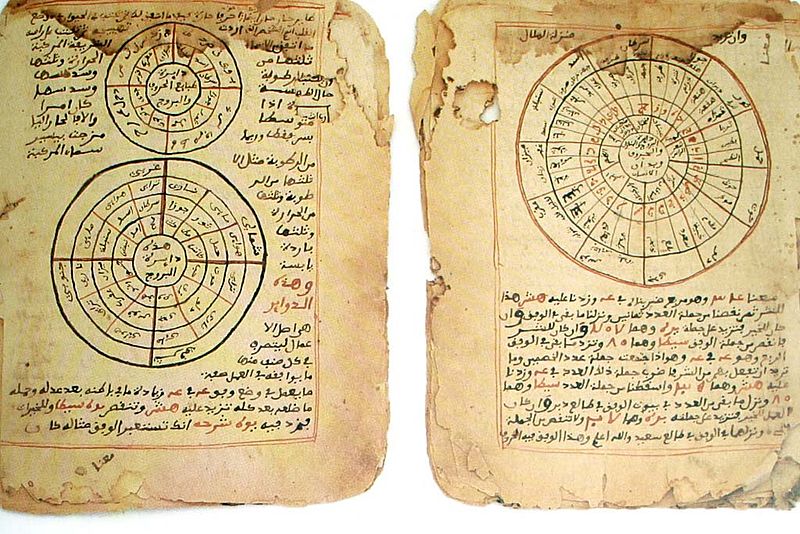

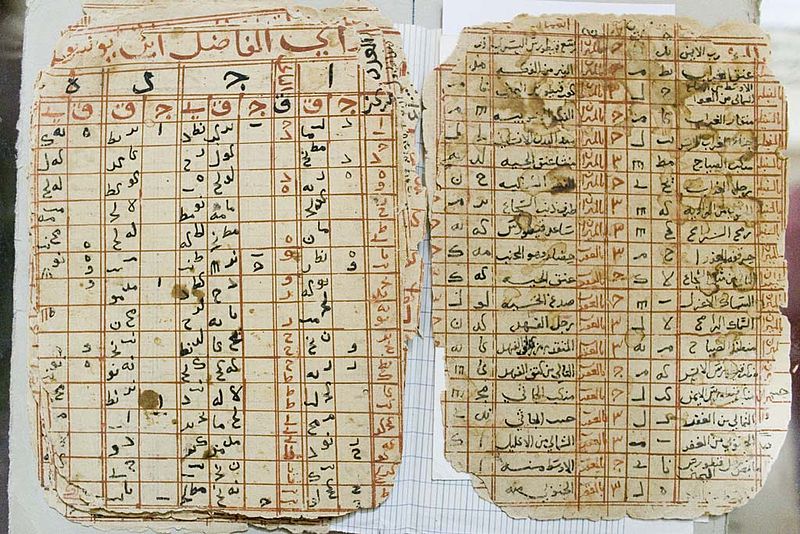

Largest Medieval Libraries; Early Literary Industry

Timbuktu and other Niger Valley cities such as Gao, Kano and Djenne remained intellectual and literary hubs for centuries, attracting

scholars from all over the world. At their height (1200-1700), such cities were widely known for their large collections of mathematical, astronomical,

religious, poetic, legal and administrative texts, including over 700,000 that have been revealed

in recent years. Timbuktu's literary culture and industry, in particular, are thoroughly

described in medieval literature.

Mohammed al-Wazzan al-Zayati (aka Leo Africanus), who visited Timbuktu in 1509, wrote that "Many manuscripts...are sold [in Timbuktu].

Such sales are more profitable than any other goods." In the Tariqh al-Sudan (1600), a book that chronicles the city's

history, Timbuktu is described as "a refuge of scholarly and righteous folk, a haunt of saints and ascetics, and a meeting

place for caravans and boats." Indeed, Mansa Musa I purchased books here and eventually constructed the Great Mosque of Timbuktu in 1326.

A majority of the so-called "Timbuktu manuscripts" and other regional books were written

in the 1300s-1600s in West African Ajami script, which has been

used since at least the 11th century to write in certain West African languages, including Kanuri, Hausa, Fulani,

Wolof and Yoruba. Although derived from the Arabic script, the two scripts differ in certain

respects. A minority of manuscripts, however, especially religious texts, were written in Arabic, Tifinagh and Hebrew scripts.

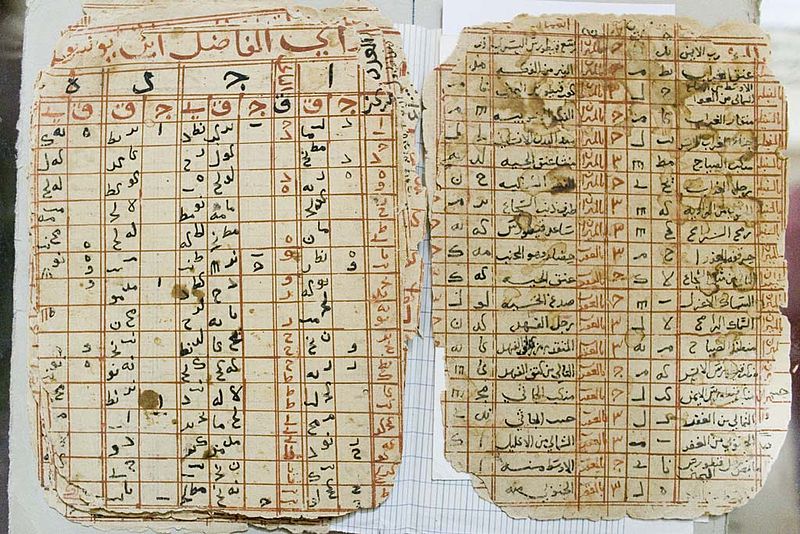

Pages from a Gao manuscript showing mathematics and astronomy (1200)

|

Pages from a Timbuktu manuscript showing astronomy tables (1200)

|